Plastic Production Comparison Tool

Compare Top Plastic Producers

This tool visualizes the annual plastic production volumes of the world's largest manufacturers. The data is based on 2025 estimates from the article.

Production Results

The biggest plastic producer in the world isn’t a company you’d find on a shelf at your local store. It’s not a brand name on a water bottle or a cereal box. It’s an energy giant that makes plastic as a side effect of making fuel - and it makes more of it than any other company on Earth.

ExxonMobil is the world’s largest plastic producer

As of 2025, ExxonMobil is the largest producer of plastic resin in the world, manufacturing over 16 million metric tons of plastic annually. Also known as ExxonMobil Corporation, the company has been expanding its plastic production since the 1970s, turning crude oil into polyethylene and polypropylene - the two most common plastics used in packaging, bottles, and films.

That’s more than double the output of its closest competitor. ExxonMobil’s plastic output equals the combined annual production of the next three largest producers: Dow, SABIC, and INEOS. Most of this plastic is made in the U.S. Gulf Coast, where cheap natural gas from fracking feeds its crackers - massive industrial plants that break down hydrocarbons into building blocks for plastic.

Why do oil companies make plastic?

It’s not about selling plastic bags. It’s about survival.

Global demand for gasoline and diesel is slowly falling as electric vehicles take over. Oil companies knew this was coming. So they shifted their bets. Plastic is the new oil. While car fuel demand drops, plastic demand keeps rising - especially in developing countries where single-use packaging is still growing. By 2030, the world could be making 600 million tons of plastic a year. Half of that will come from virgin fossil fuels, not recycling.

ExxonMobil doesn’t just make plastic. It owns the entire chain. It drills for oil, refines it into naphtha, cracks it into ethylene, and turns it into pellets that go to factories making everything from shampoo bottles to grocery bags. The company even owns some of the biggest plastic packaging brands in the U.S. through joint ventures.

How does ExxonMobil compare to other top plastic makers?

Here’s how the top five plastic producers stack up in 2025:

| Company | Annual Plastic Production (metric tons) | Headquarters | Primary Plastic Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| ExxonMobil | 16,000,000 | USA | Polyethylene, Polypropylene |

| Dow | 7,800,000 | USA | Polyethylene, Polyurethane, PVC |

| SABIC | 7,200,000 | Saudi Arabia | Polyethylene, Polypropylene, Polystyrene |

| INEOS | 6,100,000 | Switzerland | PVC, Polyethylene, Styrene |

| Formosa Plastics | 5,900,000 | Taiwan | PVC, Polyethylene, ABS |

Notice something? Four of the top five are based in countries with weak recycling systems or heavy reliance on fossil fuels. SABIC and Formosa Plastics both benefit from low-cost feedstock - natural gas in Saudi Arabia, naphtha from oil refining in Taiwan. Dow and INEOS are major players, but they still trail ExxonMobil by more than half.

Plastic production isn’t the same as plastic sales

Just because ExxonMobil makes the most plastic doesn’t mean it sells it under its own brand. Most of its output goes to packaging companies like Amcor, Berry Global, and Sealed Air. These companies turn the pellets into bottles, films, and containers that end up on store shelves.

So if you see a Coca-Cola bottle, a Nestlé snack pack, or a Walmart grocery bag - there’s a good chance the plastic inside came from ExxonMobil’s facilities in Texas or Louisiana. The brand on the product isn’t ExxonMobil, but its fingerprints are everywhere.

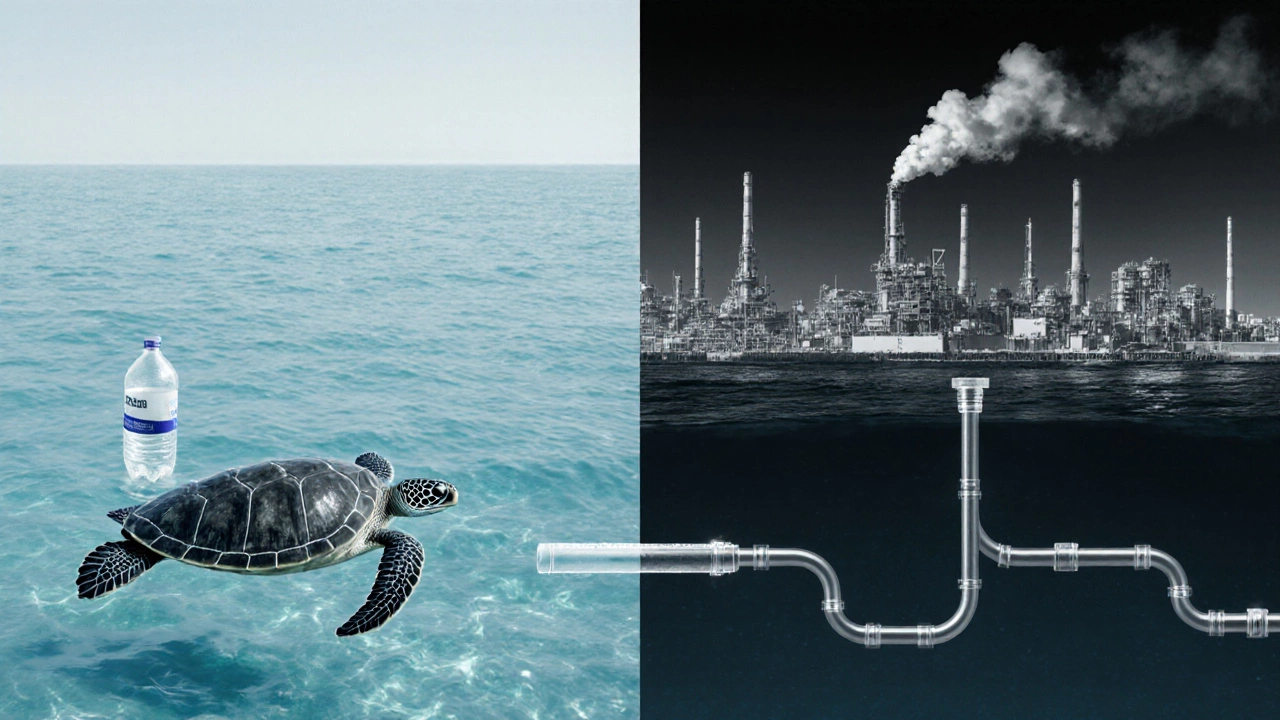

The environmental cost of being #1

ExxonMobil’s dominance in plastic production comes with a heavy price tag. In 2023, the company was linked to over 1.5 billion tons of CO₂ emissions - more than the entire country of Canada. Most of that came from making plastic, not gasoline.

Plastic production is one of the fastest-growing sources of greenhouse gases. The International Energy Agency says plastic manufacturing will account for 15% of global oil demand by 2050. And less than 10% of plastic ever made has been recycled. The rest ends up in landfills, rivers, or oceans.

ExxonMobil has publicly claimed it’s investing in recycling technology. But its own reports show over 90% of its R&D spending still goes to new fossil fuel projects - not circular solutions. In 2024, the company announced a new plant in Texas that will add another 1.2 million tons of plastic capacity. That’s more than the entire plastic output of Germany.

Who’s trying to catch up?

China’s state-owned companies like Sinopec and CNPC are expanding fast. They made 14 million tons of plastic in 2024 - close to ExxonMobil’s numbers. But China’s production is more spread out across hundreds of smaller plants, and their quality control isn’t always consistent.

Meanwhile, European companies like BASF and LyondellBasell are trying to shift toward bio-based or recycled plastics. But they still make less than half of what ExxonMobil does. The scale gap is too wide to close quickly.

Some startups claim they can disrupt the industry with algae-based plastics or chemical recycling. But none of them have scaled beyond pilot plants. The infrastructure to replace ExxonMobil’s network - the pipelines, crackers, and ports - would cost trillions. No startup has that kind of capital.

What does this mean for consumers?

You can’t boycott ExxonMobil plastic by choosing a different brand. The plastic in your yogurt tub, your phone case, or your sneakers likely came from the same source - whether it’s labeled “Eco-Friendly” or not.

Real change doesn’t come from choosing reusable bags. It comes from demanding that companies stop building new plastic plants. It comes from governments taxing virgin plastic, not just recycling it. It comes from holding the biggest producers accountable for the waste they create.

ExxonMobil didn’t become the world’s top plastic producer by accident. It did it because it could. Because oil was cheap. Because regulations were weak. And because no one forced them to change.

That’s the real story behind the number. It’s not about who makes the most plastic. It’s about who gets to decide how much we use - and who pays for the mess.

Is ExxonMobil the only big plastic producer?

No, but it’s the biggest. Other major players include Dow, SABIC, INEOS, and Formosa Plastics. Together, these five companies make more than half of the world’s virgin plastic. But ExxonMobil alone produces more than the next two combined.

Why isn’t Coca-Cola or Nestlé the biggest plastic producer?

Coca-Cola and Nestlé are big users of plastic - they buy it to package their products. But they don’t make the plastic itself. The raw material - polyethylene pellets - comes from companies like ExxonMobil and Dow. These packaging companies are customers, not manufacturers.

Can recycling solve the plastic problem?

Not on its own. Less than 10% of all plastic ever made has been recycled. Most recycling is downcycling - turning bottles into fibers for carpets or park benches, which can’t be recycled again. The system is broken because virgin plastic from oil is cheaper than recycled plastic. Until that changes, recycling won’t stop production.

What’s the difference between virgin and recycled plastic?

Virgin plastic is made from fresh fossil fuels - oil or natural gas - turned into pellets at a chemical plant. Recycled plastic is made by melting down used plastic waste and reprocessing it. Virgin plastic is cheaper, purer, and easier to use in food packaging. Recycled plastic often contains impurities and can’t be used for all applications.

Are there any countries trying to stop plastic production?

Yes. The European Union has passed laws to cap virgin plastic production and ban certain single-use items. Canada and Rwanda have banned plastic bags. But the U.S. and Saudi Arabia are still approving new plastic plants. Global action is fragmented. Without binding international rules, production will keep growing.

What’s next for plastic production?

ExxonMobil isn’t slowing down. It’s doubling down. The company plans to invest $10 billion in new plastic facilities over the next five years - mostly in the U.S. and Asia. It’s betting that demand for plastic will keep rising, even as climate pressure grows.

But the tide is turning. Investors are pulling out. Cities are banning plastic waste. Scientists are warning that plastic pollution is now a global health crisis. The question isn’t whether plastic production will shrink. It’s whether the biggest producer will be forced to change before it’s too late.